- Home

- Quntos KunQuest

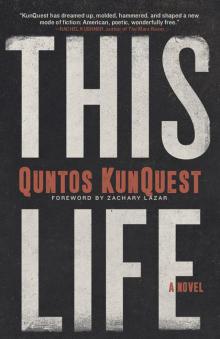

This Life

This Life Read online

THIS LIFE

THIS LIFE

A NOVEL

QUNTOS KUNQUEST

Copyright 2021 by Quntos Wilson.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without express written permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: KunQuest, Quntos

Title: This Life / Quntos KunQuest.

Description: Chicago : A Bolden Book/Agate, [2021] |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020040108 (print) | LCCN 2020040109 (ebook) | ISBN 9781572842823 (paperback) | ISBN 9781572848481 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Prisoners--Fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3611.U56 T48 2021 (print) | LCC PS3611.U56 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040108

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020040109

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Author photo by Zachary Lazar

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, incidents, and dialogue, except for specific fictionalized depictions to public figures, products, or services, as characterized in this book’s acknowledgments, are imaginary and are not intended to refer to any living persons or to disparage any company’s products or services.

Bolden Books is an imprint of Agate Publishing. Agate books are available in bulk at discount prices. Single copies are available prepaid direct from the publisher.

Agatepublishing.com

CONTENTS

Foreword

Part I

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Part II

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part III

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Part IV

Epilogue

About the Author

FOREWORD

by Zachary Lazar

I HAVE BEEN FRIENDS WITH Quntos KunQuest for such a long time—almost eight years now—that it’s strange to look back to when we first met. It was in 2013 at Angola Prison, where Quntos has been incarcerated since 1996. I had come there as a journalist to cover the rehearsals and production of a passion play, “The Life of Jesus Christ,” performed by the inmates, and Quntos was part of the sound crew. He also wrote some music for it. He was a rapper, he said, but Angola disapproved of hip-hop, unlike country, gospel, and rock, so he had to find ways to work that didn’t draw much notice, teaching himself a little guitar, a little keyboard, enough to play into a digital recorder with programmable beats and sound loops that he could rap or sing over. He wanted to write stadium songs, he told me, songs for a huge crowd, which he likened to building an outfit around a pair of shoes or a necklace, a simple central concept as the focal point of a larger composition. He was tall and everything he wore was white—white sweatpants, white hoodie, white New Balances—his sunglasses either on or down in front of his ears so the lenses cupped his chin. He said he loved books: romance novels (“Don’t tell no one”) and history. He was weird, he said, an outsider, an artist, and he sometimes had trouble getting his message across—people would start to agree with him before they really considered what he was actually saying. They agreed to agree, not even thinking about what they were agreeing with. We started talking more about books—he had been reading Machiavelli, and he said that most people don’t go deep with something like that, they just look for the main point, not the nuances or the development, and “what you do small, you do large,” he went on, meaning that people look at their whole lives and the lives of others with the same haste and shallowness.

After I wrote my magazine piece, I mentioned to Quntos I was trying to write a novel about a man serving life at Angola, and he told me he had written a novel like that himself—he would send it to me, he said, and I could “steal” from it anything I wanted. I told him I wasn’t going to steal anything but I was interested in reading his book. It arrived in my mailbox almost 20 years into his sentence, in November of 2015, the manuscript carefully handwritten in ballpoint pen, which made it a work of visual as well as literary art. What I mean is that he transcribed for me by hand a copy of his 343-page novel. When he needed italics, which he used sparingly, he would switch from print to cursive.

The story depicted an ensemble cast of characters enacting the power dynamics of prison, represented by rival crews of rappers. The action was interspersed with vivid set pieces describing daily life at Angola, written in many registers, from the African-American slang of the dialogue to the rich mix of formal and colloquial English of the narration. It was dramatic, elegant, and funny—funny in a way only possible for someone who in real life has maintained his sense of humor and joie de vivre after more than 25 years in prison.

After the first time I read it, I felt compelled to send it to my agent and my editor. It has been a long journey since then. I sent the book around for almost a year before I finally got an encouraging response from a publishing house owned by a famous rapper. They said they were interested in Quntos’s novel but they would need a typed manuscript, so I asked one of my students if he would be willing to type it and he said yes, so then I sent in the typed version in September of 2016, and in mid-November the rapper’s press came back and made an offer, with money involved. We had to educate ourselves now about logistics. For example, would Quntos have to publish under a pseudonym? How would we manage the contract and the advance and the royalties? Were there other forms of jeopardy we weren’t even foreseeing? I was concerned that the prison authorities would find ways to punish Quntos for publishing a book set at Angola, even if the publication was legal. (I had learned that it was legal from a lawyer friend, who did the research.) It was a bad winter. Sometime in January, after a lot of back and forth about the book’s title, about the difficulty of selling copies when the author couldn’t make public appearances to promote it, the rapper’s press stopped responding to me. A new president of the United States took office, the white nationalist who’d garnered more than 60 million votes. I wrote the rapper’s press one last time that February. They withdrew their offer later that day.

There’s much more to the story, but in one sense at least the story has a happy ending: After all this time, Quntos’s novel has found its proper home, Agate, where Doug Seibold had the eyes to see and the ears to hear. As the critic Jerry Saltz once said, art is for anyone; it’s just not for everyone. Readers of this novel will not find what they expect, because any novel that is a work of art bears the imprint of its maker, and makers, because they are people, are singular. Knowing them takes time. Knowing them is surprising. This knowing and these surprises are what make art valuable, even in a time that casts doubt on the very idea of any value that is not monetary but spiritual. Quntos has been incarcerated since he was 19 for a $300 carjacking in which no one was physically injured. He is serving a life sentence for this one act. This Life is a vivid portrayal of what the severity of a life sentence means, but that’s not the reason you should read it. The title explains why you should read it. It is for the clarity and insight and enormous dignity with which Quntos KunQuest conjures the singular human lives in his story.

THE INTRO

CHAPTER ONE

So much done already happened. He jus’ numb to it, all this shit: his trial, conviction, and sentence. The time he already gave up sittin’ in the parish jail. The hundreds of miles ridin’ in shackles and chains in the back of a sheriff’s van, the windows tinted and covered with some shit like chicken wire. Guarded by wack-ass correctional officers puffin’ cigarettes and blowin’ on stained coffee cups. Bad jokes and shaky laughs like he ain’t know. If anything unusual happened, they wouldn’t have hesitated to shoot. That triptriggered sump’n he wa’n’t tryna think about, but he knew: this was his slow descent to the bottom of the barrel.

All of it got him even more numb now where he stands. The numbness like ain’t nothin’ there. He looks around, without feeling, at his new surroundings. He is an admitting unit. An A.U.

There is a bunch o’ fans blowing all around. Everywhere he look he see convicts. Oldheads. Youngsters. Mostly Black, a few white dudes. Most of them wear either gray cotton joggers, jeans, or blue jeanshorts, and tanktop tees or color t-shirts. Different dudes walk past the newjack with their headphones blaring. They steal glances. Size him up. To them, he’s a fresh fish.

Boom!

The sound is followed by the noise of a bunch of people yelling and screaming, beatin’ on the walls, slammin’ chairs on the floor. His muscles tense up. He turns quickly toward the direction of the disturbance and confronts a complex of plexiglass partitions. There are about 30 dudes wildin’ out in the TV room. They’re watching an NBA game.

The A.U. walks over to the mahogany-skinned sister in a navy blue corrections uniform. She sits behind a small square table. She is the only C.O. in the dorm. He hands her his paperwork while checkin’ her nametag. Sergeant Havoc. When she opens her mouth to speak, he notices the two gold teeth on either side of her top bridge.

“You’re in bed 22,” she says and logs him on the head count.

“Where that’s at?”

She raises her head and studies him, cold-eyed. “The numbers are painted on the sides of the beds.”

The A.U. looks to his left at the bed closest to the table. He nods and turns to walk off.

She calls out, “Hey!”

“Yeah, what up?”

“The showers close at 9:00. If you go’n take one, you need to hurry up,” she snaps. Her whole vibe vaguely akin to rancor.

“I’m cool,” he says. Distracted. His senses gorge on these new surroundings.

At that, he walks toward his bed. Sergeant Havoc watches him with knowin’ eyes.

The A.U. moves through the dorm wit’ his head up. He notices pockets o’ two or three players huddled in different parts of the resting area. None of ’em are making eye contact. Well, maybe a few of them. Most are leaning in and shoo-shooing with each other.

Most of these niggas are cowards, he says to himself. Disdain. He finds out his bed is little more than a cot. He sits down and places his few things on the floor beside him. A ’vict, a’ old convict, walks up and stands in his aisle. Homedude is about 40, 45, wit’ a’ old-school shag, a salt-and-pepper beard, and bad teeth.

The ’vict says, “Check this out. The walk orderly oughta have your mattress down before lights-out. You need to remind the keyman, though. Your boxes probably won’t come ’til the morning. So—”

“—Wait a minute,” the A.U. cuts him off. “I didn’t ask you nothin’! What you want wit’ me?”

“Well, hol’ up—”

“—No! You hold up! I don’t need yo’ help. Ya best bet is to back up off me.”

The ’vict got this strained look on his face. He opens his mouth to speak and thinks better of it. He turns and walks away.

The A.U. is fuming. Who do they think he is? He’s rememberin’ all o’ those stories he heard in the parish jail. Ain’t nobody g’on fake me out, he reminds hisself. He won’t tolerate no games. He ’bout his business!

His blood pressure starts buildin’. That’s right! This is the mindset he’s more used to. It’s time to set it off in this bitch!

He jumps up and yells all kinds o’ shit at the top of his lungs. Dudes filin’ out o’ the TV and game rooms look at him like he’s crazy.

A couple o’ cats unplug the fans so they can hear what he is yellin’ about. As the hum of the fans die down, they can hear him better, like a lead guitar shredding through a break in the music.

“Yeah, that’s what I said! And I’ll represent that! … I ain’t lookin’ for no pot’nahs! I don’t need no friends! Don’t mess wit’ mines, I won’t mess wit’ yours, understand me! My name Lil Chris! If anybody got a pro’lem wit’ me, I’m down for whateva! … Wheneva! … Remember that!!”

As the ringin’ of his shouts settles on the air, everybody goes back to what they was doin’ to begin with. Nah … these cats ain’t the gladiators he’s painted into the scene. Better look again.

Like water, air ain’t still.

Wind whirls through. The wall-mounted fans start back buzzin’. He stands there wide-eyed. The voices, their echo and hum. So many people in one place, but the area is open.

His third eye workin’ overtime. It reaches to sense what his muscles can’t possibly know. It sees there are things he’ll need to peep. This need to know, he’ll get the hang of it.

In the weeks ahead, he’ll learn that while this used to be the bloodiest prison in the nation, all that has changed. The challenge of the penitentiary is more mental than physical now. Most of the savage cats that still ride are boxed away in the cellblocks and extended lock-downs where the conditions are barbaric for real. The dormitory that Lil Chris walked into is part of what is called population. Most of these inmates focus on trying to make it back to the streets. Or, at the very least, to make their stay here more comfortable, if that’s possible. The dominant perspective is that position is everything, and much too important to squander on incidental conflict. Position is always at risk where the administration has rats, squeals, trinkies, informants, or whatever in every corner. And they tellin’ everything. Period. Juggling these is a preoccupation in itself. No, he won’t receive a direct answer from these quarters. He’ll soon grasp this.

The prison’s security scheme is unit management. This has made those subject to its clutches very, very sly creatures, indeed.

Very few of the challenges Lil Chris will face in the coming times will he approach head-on.

Lil Chris figures out early on that the only place to find solitude, a chance to hear hisself think, is on his pillow, beneath his covers.

In Shreveport, Louisiana, where he grew up, the weather was often this same numbing, apathetic cold in the winter, a dry cold he inhaled thoughtlessly, that frosted his breath right in front of his face. A stiff cold that held him like a blanket in the still-life the city becomes until the scorching hot summers.

Even now, he can picture his early years in The Bottom, one of Shreveport’s oldest, roughest neighborhoods. His older sister, Michell, nursed a crush on Oreo. That one’s signature bald head, dark skin, and gold teeth. One of the infamous Bottom Boys. Them ones among Shreveport’s oldest, most organized street gangs. His beginnings.

Him only a few months past his 13th birthday, with that small band of lil street kids he started out with. Hot wires and joyrides to pass the idle hours. His mother practically as young as him. Off workin’, crisscrossin’ the country wit’ this business that did inventory for large supermarket chains. “Accucount,” or something like that.

He grew up in his grandparents’ house. Big ole whatnot shelves crowded wit’ porcelain statuettes, potted plants with running vines, and framed

family pictures. Elaborate displays of cherished old china dishes. Always the smell of cooked food. At the best of times a whiff of homemade fruit preserves kept in thick glass jars with the two-part sealing tops. Loud, boisterous voices. More akin to what you’d hear in wide country fields, yellin’ back and forth, instead o’ the close confines of a workin’ class A-frame set on a hill, sittin’ on stacked cement cinder blocks. His Baptist grandfather. Pious. Stalwart. His grandma a stern homemaker, but always wit’ a relievin’ laugh, a ready smile. She also worked as a janitor for one o’ the middle schools out in Motown, West Shreveport. Granddaddy always chased some hustle or another. A truck store, sellin’ sweets and pickled pig feet. Watermelons or some shit. There was Michell and his younger sister, Nett, along wit’ his Aunt Carrie and her two kids, Carlos and Kim. A’ old school family, a full house. He among the youngest. Runnin’ aroun’ underfoot, trampling Grandma’s flowerbeds.

His nest was one of love. From home he gained classic Black values and a basic education. And God. Still, he chose the streets. His moms was a bookworm, but his pops a’ ex-con. It was in his blood. And life was real.

So there was the streets: the pace, the pulse, the rites of passage. The pressure of it all. Crime. He picked the elements apart without thinkin’ ’bout it. Learned his lessons well and quick. By the time he turned 15 he was sump’n serious. Flanked by a different group of youngsters, some older than him. All ready to follow his lead. His confidence was boosted by survivin’ a short but hard stint in juvenile for weapons possession.

Back in his own hood, Lakeside. Streets a mixture of black and white. Tar backroads lined by ditches on both sides. Paved concrete thoroughways, curbed and sidewalked. Rows of frame houses, almost all fronted by picture windows. Low-rate market. Mortgaged or rented. Honest, hard workers’ dwellings weevilled by crack houses. Everybody struggling. Some much more than others.

The block, peopled by prayers and sinners. Churches and liquor stores switchin’ up on every corner along the avenue. Scented by tree sap, treaded acorns, sprinkled pecans. Discarded liquor bottles and corner store feedbags. Baby diapers. Dog, cat, and chicken shit. Consumer brand smell-goods. Cologne and perfumes and sweat.

This Life

This Life